Groups, Clusters, and Superclusters

Most galaxies are too far away to see with the naked eye. But when a powerful telescope points toward a seemingly dark region of the sky, where light from distant places is not obscured by nearby stars, the view is breathtaking. NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has captured some spectacular deep field images—composite time-exposure photographs of galaxies billions of light-years away. A deep field image created in 2012, the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field (XDF), was compiled from more than 2,000 photographs of the same dark patch of sky. The camera shutter was left open for an average of more than 15 minutes per photo (a total exposure time of 23 days) to detect even the dimmest light from the most distant galaxies.This information and many further details are provided on NASA’s website, here. Then these photos were merged into a single image. What did this composite image reveal, in that dark part of the sky? Take a look:

These colorful speckles of light aren’t stars. They are galaxies, each consisting of millions or billions of stars! Click here for a zoomable version of this photo. Click here for more information about the Hubble XDF.

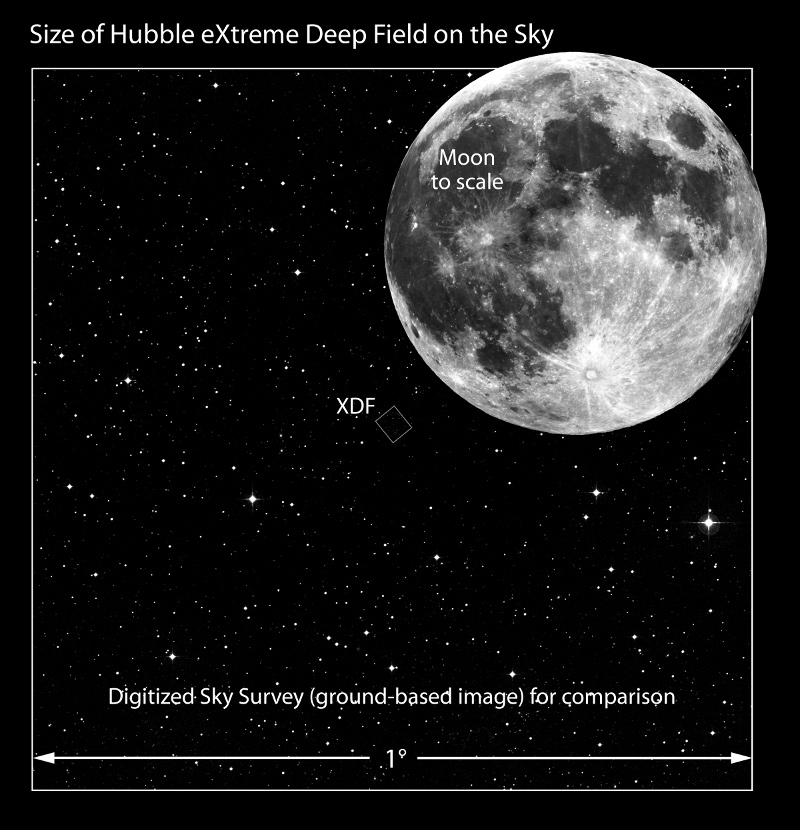

Space is teeming with colorful galaxies, almost endlessly, in every direction. Using this deep field image, astronomers counted roughly 5,500 galaxies within the camera’s narrow field of view, which is less than 2.4 arcminutes (0.04 degrees) wide.Details are given on the Hubble website, here. To put this in perspective, imagine standing under the night sky and holding up your pinky finger at arm’s length. The width of your little finger covers a patch of sky more than 60 arcminutes (1 degree) across. That’s 25 times wider than the Hubble camera’s field of view. In other words, the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field image shows a patch of sky less than 1/25th the width of the region hidden by your little finger. And there are more than 5,000 galaxies in that tiny segment of the sky!

The tiny rectangle in the center is the region seen in the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field (XDF) image.

So, how many galaxies are there in the whole universe? No one knows. There are, almost certainly, many galaxies so far away that their light hasn’t yet reached us. But astronomers have been able to estimate the number of galaxies in the observable universe—that is, the region of the universe close enough for its light to have reached us by now. The total number of galaxies in the observable universe is at least 100 billion, according to conservative estimates, and possibly much higher. (One recent estimate places the number around 2 trillion.) That’s how many galaxies could potentially be detected from Earth; no one knows how far the universe extends beyond the range of the light that has reached us so far.

Throughout the observable universe, galaxies are gathered together in groups or clusters. (Smaller collections of galaxies are usually called groups; larger ones are called clusters.) Groups and clusters, in turn, are found together in even larger structures called superclusters. Our own Milky Way Galaxy belongs to the Local Group, which also includes the Andromeda Galaxy, the Triangulum Galaxy, the Large Magellanic Cloud, and about 50 dwarf galaxies. The Local Group, in turn, belongs to the Local Supercluster (sometimes called the Virgo Supercluster)—an enormous collection of over 100 galaxy groups and clusters, spreading over a region of space more than 100 million light years across.See here for more information.

This computer-simulated video begins with a view of our planet then zooms out to the edge of the observable universe, showing the large-scale structure of galaxies, clusters, and superclusters.

The Local Supercluster, in which our galaxy resides, is just one of millions of superclusters spread throughout the observable universe. And remember, the observable universe isn’t the whole universe. There are probably many more galaxies, clusters, and superclusters beyond the distance light has traveled since the beginning of time.

Speaking of the beginning of time… some important discoveries in astronomy and cosmology seem to imply that the entire physical universe—and even time itself—had a beginning. Let’s talk about that.